The Personality DNA of Leaders

In Brief

- The Big Five personality traits is the most accurate taxonomy of personality that psychologists have been able to prove to any reliable degree.

- It outlines five different personality traits, namely Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.

- We are all a unique combination of these five, but strong leaders tend to have a specific distribution of these traits.

- The best combination of traits depends on the company, where they are at in their evolution, where they need to get to, and in what timeframe.”

The Details

From all of the research done in the past century on behavior and performance in the workplace, aside from research on intelligence, none has proven to be more valid and reliable across cultures as the Big Five personality traits (DeYoung et al. 2011). Yes, it has its flaws, but the Big Five is the best attempt yet to create a taxonomy of personality traits that best describes us all as individuals. By way of a brief introduction to each of the five traits, Judge et al. (2002) provide a good summary:

“Openness to Experience is the disposition to be imaginative, nonconforming, unconventional, and autonomous. Conscientiousness is comprised of two related facets: achievement and dependability. Agreeableness is the tendency to be trusting, compliant, caring, and gentle. Extraversion represents the tendency to be sociable, assertive, active, and to experience positive affects, such as energy and zeal. Neuroticism represents the tendency to exhibit poor emotional adjustment and experience negative effects, such as anxiety, insecurity, and hostility.”

Openness

Openness tends to indicate people who are curious, imaginative, and creative problem solvers (Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2005). People who score highly on this dimension have a greater tendency towards cognitive exploration and also manifest higher levels of cognitive flexibility and divergent thinking (DeYoung, Peterson, & Higgins, 2005). This is a critical trait for leaders, and for me, the defining Big Five trait that separates visionary leaders from managers. Managers don’t necessarily need to be high in openness. They don’t need to have the ideas or be great problem solvers. They have to complete tasks and make sure teams of people are doing what is asked of them, all within the confines of a specific set of rules. That is more to do with conscientiousness rather than openness.

Openness is highly linked to creativity. Creativity includes ideas and problem solving and is highly correlated with intelligence. That’s not to say that intelligent people are all creative, but one can make the argument that intelligent people know how to solve problems, at least certain types of problems. It is certainly true that creative people tend to be intelligent, but again, not on all dimensions of intelligence all of the time. Think about a spectrum between outrageously inventive entrepreneurs at one end and extremely good operations managers at another end. The former will be higher in openness, and the latter will be high in conscientiousness but not necessarily high in openness.

Conscientiousness

The extent to which someone is conscientious, which implies they are hardworking, organized, efficient, and self-disciplined, has emerged as a strong predictor of success in the workplace (Barrick & Mount, 1991). One study even showed that self-discipline, linked to conscientiousness, was twice as effective as IQ at predicting academic performance (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005). It goes without saying that if you work hard, you’ll get ahead most of the time. Conscientiousness doesn’t override IQ, though. For example, someone with an IQ of lower than 90, who would, by definition, find learning hard in general, will not be able to just work really hard and become a doctor unless their IQ score was wrongly marked. Furthermore, conscientiousness without the right balance of other traits does not by itself predict strong leadership skills. In other words, for someone to have strong leadership skills, they cannot just be hard working. There probably isn’t a world leader out there that doesn’t work hard, but that doesn’t make them great leaders all of the time.

Neuroticism

After conscientiousness, rating low for the trait neuroticism, or in other words, rating high for emotional stability, has been shown to be a big predictor of success in the workplace (Salgado, 1997). Low neuroticism has also proven to be a good predictor of job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Thoresen et al., 2003). This makes sense when you consider how much pressure leaders can be under, especially when they’re running enormous companies. Many of us will also know those people in our social life or work environment that just criticize everything, are always having the “worst day ever,” and can’t understand why things “always happen to them.” Those people, if you haven’t guessed, will rate high for trait neuroticism. That’s not a good score, by the way. Leaders, by contrast, tend to be very calm under pressure and in a crisis, which, again, makes logical sense.

Extraversion

A study by Gough (1990) found that naturally emerging leaders in groups were described with adjectives like “active, assertive, energetic, and not silent or withdrawn” (Gough, 1990). These are the characteristics of extraverts. Indeed, Gough (1990) found that both of the major facets of extraversion—dominance and sociability—were related to self and peer ratings of leadership (Judge et al., 2002). It’s important to note that this does not mean that those that are not extraverts cannot make good leaders. It often comes down to how we interpret the word “extravert.” Many of us imagine loud attention seekers when we hear this word, and that just isn’t what this is.

On a scale going from introvert to extrovert, individuals can be anywhere on that scale, and their behaviors will not always represent where they naturally fall on that scale. Consider some of the most successful leaders of our time who are considered to be introverted, like Bill Gates, for example. Although he is an introvert, he’s still getting on stage in front of thousands of people. Also, people closer to the introvert side of the scale tend to be less impulsive and, therefore, naturally, take more time to think, which is critical in leadership when considering some of the enormous decisions they have to make.

So, for me, the notion that leaders must be extravert is just not true. Perhaps it’s more fitting to suggest that leaders have to, at times, do things that extraverts would be more known to enjoy, like speaking in front of people, for example. With that, it may be fairer to say that leaders have to be able to demonstrate moderately extraverted behavior when required, but if they are otherwise introverts, it doesn’t impede their ability to succeed in any way.

Agreeableness

According to the studies, agreeableness appears to carry the most amount of ambiguity when it comes to leadership effectiveness, which is really saying something. It would be too simple to state that effective leaders tend to be less agreeable because they have to make decisions and know they can’t please everyone. Extremely agreeable people are pleasers and want everyone to be happy, and it’s fair to say that this would not make for a good leader. However, at the other end of the spectrum are those who are entirely disagreeable, which also doesn’t make for a very inclusive way of managing people.

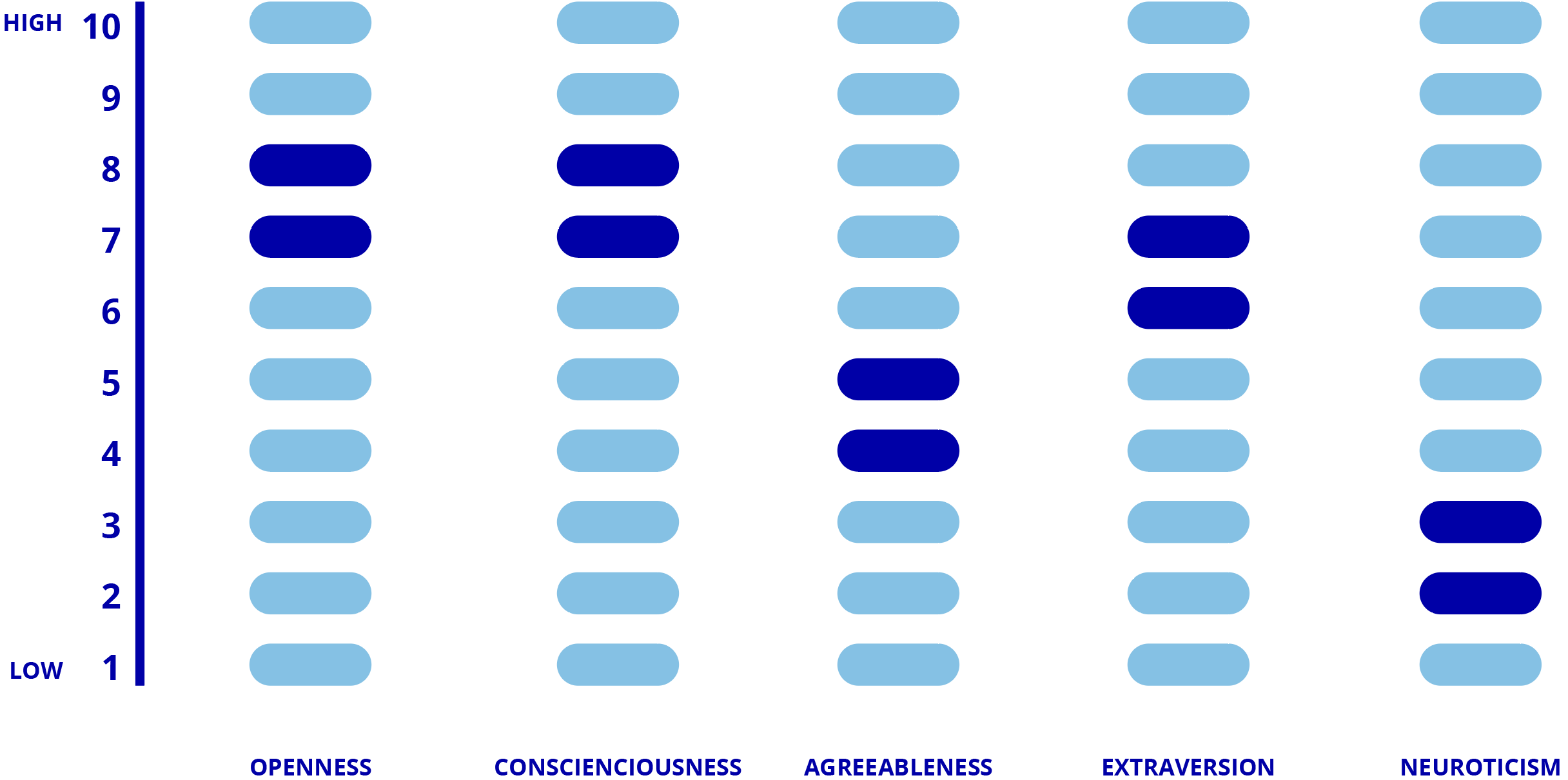

Figure 1: Optimal Leadership DNA

So what makes the optimal leader? Figure 1 shows what I understand to be the optimal leadership DNA in terms of the Big Five. This is my take, based on the psychometric literature on what the optimal balance of the Big Five traits is for leadership. I’ve taken each of the five traits and applied a scale of one to ten, and suggested a sweet spot for each one consisting of two positions for each. From this chart, we can see that a good leader is typically high in openness, high in conscientiousness, moderate in agreeableness, moderate to high extraversion, and low in neuroticism. This is entirely consistent with the psychometric studies.

Leaders will typically be a seven or eight in openness as openness relates to ideas and problem solving, and this is where great leaders come into their own. They don’t have a textbook or someone telling them what to do. They will no doubt have trusted lieutenants advising them what to do, but the buck stops with them, and they have to make the most difficult decisions in the company. They’re typically a seven or an eight in conscientiousness as they have to get things done but not in such a rigid fashion that they fail to adapt. They will most certainly want their CFO to be a nine or a ten. They will ideally be on the lower side of moderate in agreeableness, but not so low that they don’t know how to listen or be open to other ideas. Extraversion will be moderate to high, at least when called for, in order to develop the right sorts of relationships with people and also to be able to lead and inspire in general. Neuroticism should definitely be low but perhaps not a one. They cannot be emotionally detached from the world but should absolutely be calm under pressure and generally be positive.

This list is not prescriptive. For example, you have great introverted leaders who are not high on extraversion at all. You have very conscientious leaders who may not be extremely high in openness. Different companies at different stages of evolution will have different requirements of leaders as they relate to this mix, so the optimal leadership DNA is a generalized illustration based on the actual studies that have been conducted. If you’re a startup, your leader, who is likely to be the founder, will typically be very high in openness but may not be extremely high in conscientiousness, for example.

The real answer to the question of what mix of personality traits makes a good leader is, “It depends on the company, where they are currently in their evolution, where they need to get to, and in what timeframe.” It is probably fairer to suggest what definitely will not make a great leader, and that is someone who is very high in agreeableness, very high in neuroticism, very low in openness, and very low in conscientiousness.

It is certainly fair to say that, to date, we do not have a better way of explaining personalities. Sure, it’s not the perfect explanation, but nobody ever said it is. Humans are so unbelievably complex as individuals, with so many factors affecting us growing up, with so many influences and so many human interactions, that we may never fully account for personality in its entirety. What we can do, though, is take more time to better understand and accept ourselves, our limitations, our possibilities, and our preferences, much of which can be better understood with a deep dive into the Big Five model.

Despite the complexities of humans and regardless of how different we claim to be, the reality is we are mostly the same, at least from a Big Five personality perspective. If you were to map out the distribution of traits among men alongside the distribution of traits among women, for example, for the most part, they overlap. It is only when we get to the outer edges of these distribution curves that we see the differences being more prevalent. This means that within a significant enough dataset of men and women, from a personality trait perspective, most people’s profiles will be indistinguishable. What this means is, generally speaking, men or women are not better than the opposite sex at leading or even just being a useful contributor in the workplace. They are generally the same, but it depends on the person; it depends on the individual human, not their gender. A good leader is a good leader. We should stop wasting our time debating which gender or ethnicity or whatever group(s) we decide we belong to leads better. The ideal personality DNA of good leaders may not be entirely conclusive, but for sure, it’s not defined by the concentration of our melanin in our skin or the pronouns we prefer to be addressed as. Good leadership is in the DNA of those that are good leaders, period.

About The Author

Fraser Hill is the founder of the leadership consulting and assessment company, Bremnus, as well as the founder and creator of Extraview.io, an HR software company aimed at experienced hire interview and selection in corporates and executive search firms. His 20+ year career has brought him to London, Hong Kong, Eastern Europe, Canada, and now the US, where he lives and works. His new book is The CEO’s Greatest Asset – The Art and Science of Landing Leaders.

References

Barrick, M., Mount, M. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.

Carson, S., Peterson, J., Higgins, D. (2005). Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure of the Creative Achievement Questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal. 17(1):37-50.

DeYoung, C., Quilty, L., & Peterson, J. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 93. 880-96.

DeYoung, C, G., Hirsh, J. B., Weisberg, Y. J. (2011). Gender Differences in Personality across the Ten Aspects of the Big Five, Frontiers in Psychology. 2: 178.

Duckworth, A., Seligman, M. (2005). Psychol Sci. Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents.

Gough, H. (1990). Testing for leadership with the California Psychological Inventory. West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America.

Judge, T., Heller, D., Mount, M. (2002). Five-Factor Model of Personality and Job Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Salgado, J. F. (1997). The five factor model of personality and job performance in the European community. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82.

Thoresen, C. J., Kaplan, S. A., Barsky, A. P., Warren, C. R., & De Chermont, K. (2003). The Affective Underpinnings of Job Perceptions and Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review and Integration.